Sospiros Vibrato emerged from an ambitious vision to redefine what a modern fragrance could be while still honoring the craft’s timeless traditions. The creative team set out to translate the concept of “vibrato” from the realm of music into a language of scent—capturing the sensation of movement, fluctuation, and emotional resonance. In musical terms, vibrato adds depth, warmth, and expressiveness to a note, and the creators sought to achieve the same in an olfactory form. This meant working with an idea that was as much about feeling as it was about aroma, seeking to evoke subtle shifts in mood and perception throughout the day. The result was a perfume designed to be experienced like a living performance, with a beginning, middle, and end that each reveal something new.

The name “Sospiros” carries connotations of breath, sighs, and longing—sensations that speak to the intimacy and emotional depth the fragrance aims to capture. Pairing it with “Vibrato” created a union of softness and energy, of contemplation and dynamism. This duality became the guiding principle of the scent’s development. The inspiration extended beyond music to visual arts and even literature, where layers of meaning and shifting interpretations mirror the layered nature of the fragrance itself. The team envisioned a scent that could connect deeply with wearers on a personal level, becoming part of their own story and memory.

The Creative Process and Artistic Vision

Crafting Sospiros Vibrato was an intricate and deeply collaborative process involving perfumers, designers, and sensory researchers. The starting point was an exploration of the emotional triggers embedded in specific aromatic molecules—understanding which notes could bring a sense of brightness, which could deepen the mood, and how these elements might interact. From there, an initial palette was assembled, drawing on both rare natural extracts and carefully chosen synthetics to ensure a broad range of expression. Over many months, the team experimented with countless variations, adjusting proportions, altering sequences, and refining textures until the fragrance felt both balanced and alive.

The artistic vision for Sospiros Vibrato centered on creating an olfactory performance that would adapt and respond to the wearer’s presence and environment. The goal was not a static scent, but one that evolved, much like a piece of music interpreted differently each time it is performed. This required meticulous attention to transitions between top, heart, and base notes, ensuring that each stage offered its own distinct beauty while remaining connected to the whole. Longevity, projection, and emotional impact were treated with equal importance, resulting in a scent that feels intimate yet noticeable, sophisticated yet approachable.

Key Notes and Olfactory Profile

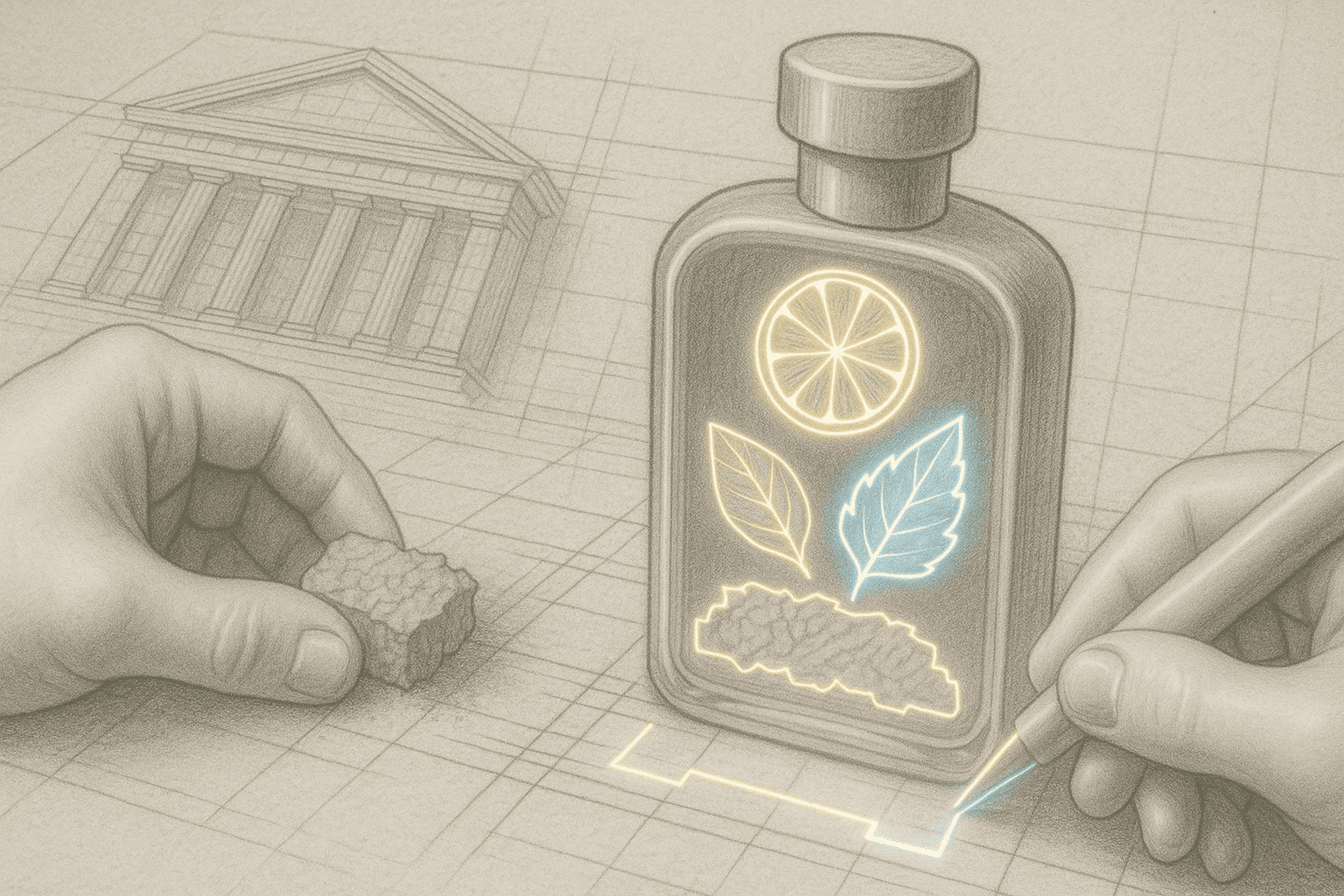

From the very first spray, Sospiros Vibrato presents an opening designed to uplift and intrigue. Bright citrus essences shimmer against crisp green nuances, creating an almost sparkling introduction that awakens the senses and sets a lively tempo. These top notes are crafted to provide instant freshness without fading too quickly, allowing them to gracefully segue into the heart of the fragrance. As the initial brightness begins to soften, a bouquet of elegant florals emerges—rich yet airy, blending delicate petals with subtly sweet undertones. This heart phase is where the fragrance reveals its romantic side, offering depth without heaviness.

The base of Sospiros Vibrato anchors the entire composition with a warm, resonant foundation. Smooth, refined woods bring structure, while velvety musks add softness and sensuality. Gentle spices weave through these deeper notes, introducing a quiet complexity that lingers on the skin. The transitions between these layers are seamless, creating a continuous evolution that keeps the wearer engaged. Whether in motion or at rest, the fragrance responds with shifts in tone and texture, ensuring that it feels alive throughout the day. The result is a profile that is at once dynamic and harmonious, reflecting its musical inspiration.

Packaging Design and Visual Identity

The design of Sospiros Vibrato’s packaging was approached as an extension of the fragrance’s narrative. Flowing lines echo the undulating motion of vibrato in music, while carefully chosen textures add depth to the visual and tactile experience. The color palette combines sophistication with vibrancy, using harmonious contrasts to reflect the dual nature of the scent—its blend of energy and elegance. Metallic accents catch the light subtly, suggesting a modern refinement without overwhelming the design’s graceful simplicity. Every element, from the curvature of the bottle to the composition of the label, was considered in relation to the scent’s story.

Equally important was the sensory feel of the packaging in the hand. The bottle’s weight conveys quality and presence, while the finish offers a smooth, luxurious touch. Even the sprayer was engineered for precision, ensuring a fine mist that delivers the fragrance evenly and elegantly. This attention to detail reinforces the idea that Sospiros Vibrato is not just a scent, but a full sensory experience. By uniting visual artistry with ergonomic function, the packaging invites anticipation before the fragrance even reaches the skin, creating a seamless link between form and essence.

Reception and Influence in the Perfume Community

Upon its introduction, Sospiros Vibrato quickly attracted attention for its rare balance of originality and accessibility. Perfume enthusiasts and critics alike praised its nuanced construction, noting how each stage of its development on the skin seemed thoughtfully composed. It was recognized as a fragrance capable of making a statement without dominating the wearer’s presence, adaptable enough for both daytime sophistication and evening elegance. Many reviewers commented on its emotional resonance, describing it as a scent that felt personal and memorable.

Its influence extended beyond individual admiration, shaping discussions in the perfume community about the potential for fragrances to act as immersive art forms. Sospiros Vibrato encouraged other creators to explore more complex narrative structures in scent, blending tradition and experimentation in new ways. For emerging perfumers, it became a benchmark of how technical precision can coexist with artistic storytelling. Over time, its reputation has solidified as an example of how modern perfumery can create works that are not only beautiful but culturally and creatively significant.

The Lasting Legacy of Sospiros Vibrato

The enduring appeal of Sospiros Vibrato lies in several interconnected qualities that define its legacy:

- A seamless blend of classical craftsmanship and contemporary innovation, demonstrating how heritage and progress can coexist.

- An evolving olfactory structure that offers new experiences throughout the day, rewarding close attention and repeated wear.

- Packaging that elevates the fragrance into a full sensory journey, where sight and touch are as considered as scent.

- Strong ties to artistic inspiration from music, visual arts, and literature, enriching its conceptual depth.

- A tangible impact on creative directions in perfumery, encouraging bolder and more narrative-driven compositions.

Through these qualities, Sospiros Vibrato has transcended its role as a product to become a cultural and creative reference point. It continues to inspire both those who wear it and those who create, ensuring its influence will persist in the evolving dialogue of modern fragrance.

Questions and Answers

Answer 1: To capture the expressive movement of musical vibrato in a scent, blending tradition with modern creativity.

Answer 2: By carefully balancing top, heart, and base notes to transition seamlessly and change character over time.

Answer 3: A lively citrus-green opening, an elegant floral heart, and a warm, woody-musky base with subtle spices.

Answer 4: Through flowing design lines, refined textures, a harmonious color scheme, and precise functional details.

Answer 5: It inspired greater focus on narrative-driven compositions and the integration of artistic concepts into scent creation.